Fabs

I built these colorful windows for a certain unnamed member of Guns and Roses. Rain glass, simple diamond pattern, but 3/8” lead was tricky to weld!

It’s standard to use a soldering iron to fabricate leaded windows, the same kind engineers use on PCBs. The ideal leaded joint is soldered in two passes, anything more and the joint will look lumpy and overworked.

First, you tin the surface of the lead with a light coat of solder. Then you come through with another thin layer, this time with an eye for detail and structural integrity.

The wider the lead, the harder it is to get completely flat and even joints. I’m happy with my results though, and so was the customer!

The transom was a run-of-the-mill design with a nice stock bevel pattern, notable really only because I saw the project all the way through. I drew up the pattern by hand based on customer specs, and I installed it myself, over their front door.

I built these colorful windows for a certain unnamed member of Guns and Roses. Rain glass, simple diamond pattern, but 3/8” lead was tricky to weld!

It’s standard to use a soldering iron to fabricate leaded windows, the same kind engineers use on PCBs. The ideal leaded joint is soldered in two passes, anything more and the joint will look lumpy and overworked.

First, you tin the surface of the lead with a light coat of solder. Then you come through with another thin layer, this time with an eye for detail and structural integrity.

The wider the lead, the harder it is to get completely flat and even joints. I’m happy with my results though, and so was the customer!

The transom was a run-of-the-mill design with a nice stock bevel pattern, notable really only because I saw the project all the way through. I drew up the pattern by hand based on customer specs, and I installed it myself, over their front door.

Repairs

I handle all kinds of unique will-call repairs, which is a rewarding part of the job. Hobbyists love to work with copper foil (see rose windows) and their creations come through all the time. Copper foiling is a technique where you adhere thin strips of copper foil to the edges of your glass and solder the seams. The result looks a lot like leaded glass, and when a piece breaks it's fairly easy to desolder and remove. I replaced three rose petals for each of these repairs, but I couldn’t tell you which!

The two doors are examples of more traditional leaded glass, viz., glass slotted into strips of lead, called “came” and puttied. The arched window was a full re-lead (reuse the glass and rebuild the window). The French doors were a tear repair (cut the window and replace broken pieces), which had to be surgical given the exquisite overlay work.

I handle all kinds of unique will-call repairs, which is a rewarding part of the job. Hobbyists love to work with copper foil (see rose windows) and their creations come through all the time. Copper foiling is a technique where you adhere thin strips of copper foil to the edges of your glass and solder the seams. The result looks a lot like leaded glass, and when a piece breaks it's fairly easy to desolder and remove. I replaced three rose petals for each of these repairs, but I couldn’t tell you which!

The two doors are examples of more traditional leaded glass, viz., glass slotted into strips of lead, called “came” and puttied. The arched window was a full re-lead (reuse the glass and rebuild the window). The French doors were a tear repair (cut the window and replace broken pieces), which had to be surgical given the exquisite overlay work.

Church Windows

Church windows often demand the most technically complex and precise repair work. There are also usually like twenty of them, so accurate labor estimates become the difference between profit and loss.

The ones pictured came from a customer who had purchased a church in Ballard to live in. I think he was an atheist. The windows are somewhere between 70-100 years old, right around the time the lead begins to develop fissures. Our job was to fix the cracked pieces, replace the broken lead, and clean decades of candle smoke from the textured side of the glass.

Fixing the broken pieces in the center of the windows was a challange, especially since we were operating under a limited budget. What saved time was a beautiful technique called the peel repair. Using lead snips we separated the face of the lead came and replaced the broken glass underneath. Then we sweat soldered a new face onto the existing lead. This proved much faster than tearing the window open.

Sweat soldering leaded windows requires a good deal of finesse. Your soldering iron must apply sustained heat to the new lead face (using a buffer, like a strip of aluminum cut from a can) while you hope and pray it mates with the old lead underneath. If you’ve properly beaded both segments you can expect them to come together in a few minutes, depending on the heat setting of your iron. This is a nervy process. The longer you keep your iron down, the higher the risk of a thermal fracture to the glass underneath. You would never want to do this to panels from the Chartres Cathedral, but the customer said fast, fast, fast! And my soldering iron aimed true. It turned out well.

Church windows often demand the most technically complex and precise repair work. There are also usually like twenty of them, so accurate labor estimates become the difference between profit and loss.

The ones pictured came from a customer who had purchased a church in Ballard to live in. I think he was an atheist. The windows are somewhere between 70-100 years old, right around the time the lead begins to develop fissures. Our job was to fix the cracked pieces, replace the broken lead, and clean decades of candle smoke from the textured side of the glass.

Fixing the broken pieces in the center of the windows was a challange, especially since we were operating under a limited budget. What saved time was a beautiful technique called the peel repair. Using lead snips we separated the face of the lead came and replaced the broken glass underneath. Then we sweat soldered a new face onto the existing lead. This proved much faster than tearing the window open.

Sweat soldering leaded windows requires a good deal of finesse. Your soldering iron must apply sustained heat to the new lead face (using a buffer, like a strip of aluminum cut from a can) while you hope and pray it mates with the old lead underneath. If you’ve properly beaded both segments you can expect them to come together in a few minutes, depending on the heat setting of your iron. This is a nervy process. The longer you keep your iron down, the higher the risk of a thermal fracture to the glass underneath. You would never want to do this to panels from the Chartres Cathedral, but the customer said fast, fast, fast! And my soldering iron aimed true. It turned out well.

Works in progress

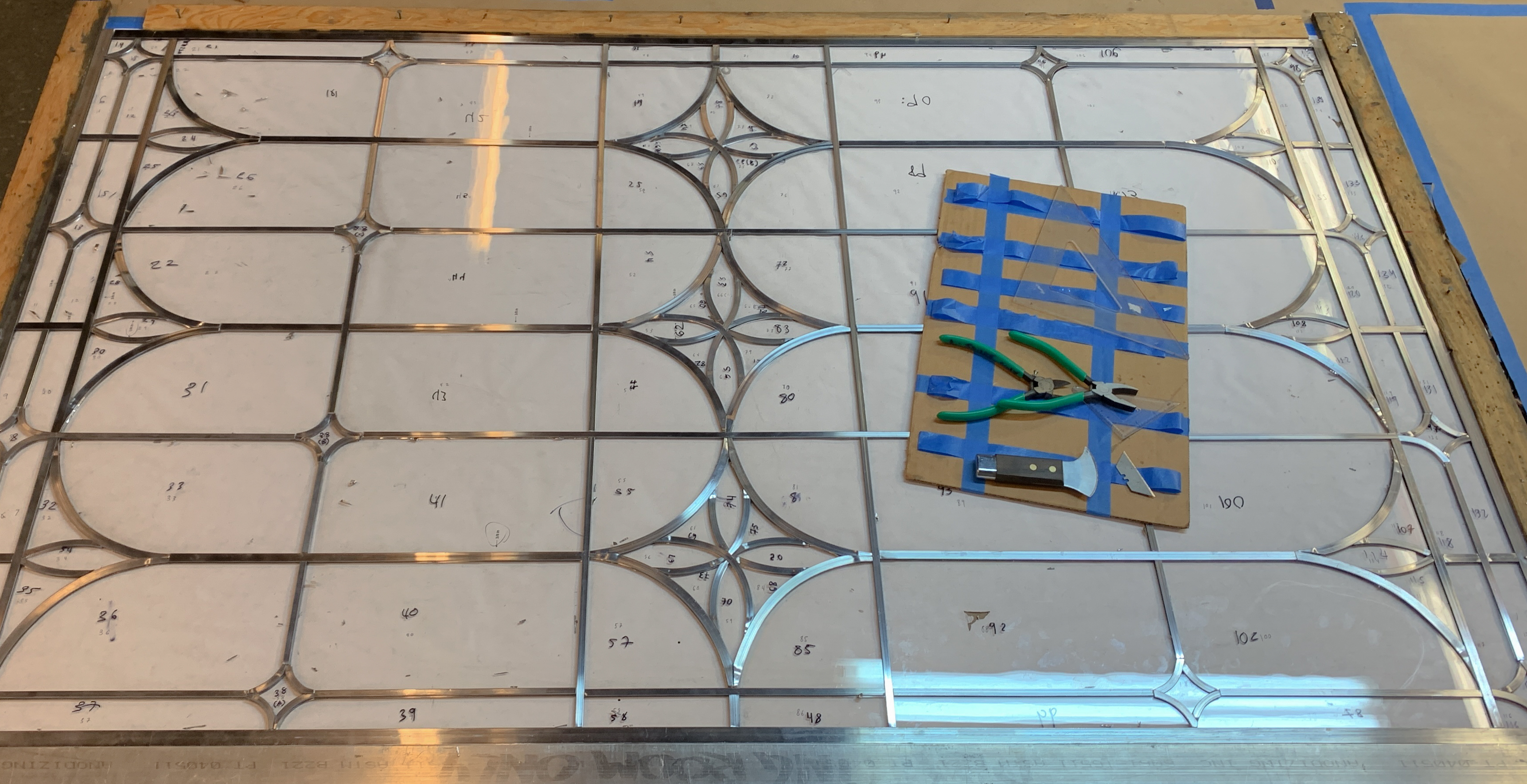

Complex and fairly large (50”x73”) transom. Stay tuned...

Complex and fairly large (50”x73”) transom. Stay tuned...